Berkeleyan

Clark Kerr remembered

Speakers laud his legacy for higher education — and warn that it is in peril

![]()

| 25 February 2004

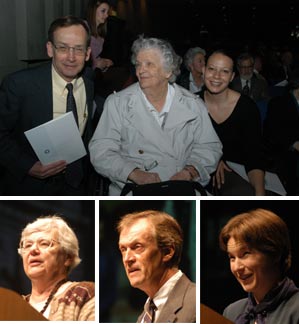

| |  Top photo from left: family members Clark E. Kerr, Kay (Mrs. Clark) Kerr, and granddaughter Sevgi Fernandes. Below, from left: Kerr's research associate of many years, Marian Gade; UC president Robert Dynes; Kerr’s granddaughter, Amber. Peg Skorpinski photos |

At the close of the first volume of his memoirs, The Gold and the Blue, the late Clark Kerr stated, without equivocation, “As goes education, so goes the future of the state of California.” That conviction resonated in the testimonials to Kerr’s lifetime of contributions to the University of California in particular, and higher education in general, that punctuated last Friday’s campus memorial to him. The former Berkeley chancellor and University of California president died Dec. 1 at the age of 92.

Yet also resonant were echoes of the rhetorical question Kerr raised in the very next paragraph of his 2001 book: “Has paradise already been lost, or is it in the process of being lost?” Paradise, for Kerr, was the 1960 Master Plan for Higher Education in California, with its promise of higher education for all citizens qualified to profit from it. Kerr, the chief architect of that plan, lived to see it threatened by the straitened condition in which UC currently finds itself. Those concerns colored the appreciative and admiring remembrances at the memorial.

Calling Kerr “the father of the modern University of California,” Berkeley Chancellor Robert Berdahl said the Master Plan was one of his two greatest achievements, along with expanding UC to a nine-campus system.

“It’s an achievement that has never been duplicated in any state of the union,” said Berdahl of the plan. “It is an achievement that could not be duplicated today, even here in California. But it became the gold standard for public higher education in America, and the envy of the nation. Without Clark Kerr it would not have happened.”

The continued viability of that plan has been called into question by several years of budget cuts, with more on the near horizon — cuts so severe that, for the first time in decades, qualified students may be turned away from UC beginning next fall. Berdahl’s own rhetorical question before the Zellerbach Hall audience — “Can Clark Kerr’s bold vision of the University of California and higher education in California be sustained?” — was clearly informed by his own keen familiarity with the range of threats confronting the system.

The day’s other tributes to Kerr, lauding his decades of service to higher education, put that air of caution and concern in context. UC President Robert Dynes noted that the University of California today is the leading public university in America (“and some would say,” he added pointedly, “that it is the leading university, full stop”). “It is hard to overstate the importance of Clark Kerr’s contribution” to that reputation, Dynes said. The Kerr era, in addition to being one of “intelligent and sensitive planning directing [UC’s] growth,” was an era of “new promise for California and its people,” Dynes affirmed.

Kerr’s enduring legacies, Dynes continued, are academic excellence and accessibility. “The manifestation of these two things are literally all around us — in the students, in the faculty, the staff, our graduates, and the university’s deep daily impacts on the health, economy, and social welfare of California,” he said. “I think it’s worthwhile to consider the things a society can accomplish when it makes up its mind that public higher education is a priority and a good investment in the future.”

Solutions ‘in a world of conflict’

The lineup of speakers described a man of exemplary work habits, of dedication and persistence, and, possibly above all, of an enduring commitment to “the pursuit of peaceful solutions in a world of conflict” (as Kerr himself wrote) and a faith in the power of reason to settle disputes.

“For a quiet pacifist from a Quaker college … who never sought or much enjoyed conflict, Kerr often found himself in the midst of [it],” said Berdahl. “First as a labor mediator, then as a university administrator, he retained the conviction that all problems have solutions, that all conflicts can be resolved.”

As the day’s speakers and the lively video biography screened at the ceremony attested, Kerr faced no shortage of conflicts between the time he joined the Berkeley faculty in 1945, as head of the new Institute of Industrial Relations, and the date of his dismissal as UC president nearly 22 years later. During those years — six of which he spent as Berkeley’s first chancellor — he was involved intimately with a wide range of issues and controversies, including the Loyalty Oath crisis of the early 1950s, the Free Speech Movement of 1964, and the rise of student activism in the 1960s generally. In the judgment of Governor Ronald Reagan and his allies on the Board of Regents, it was Kerr’s “failure” to stem student unrest that led to his dismissal as UC president — and the utterance of his most-oft-repeated witticism: “I left the job the same way I came into it: fired with enthusiasm.”

Kerr’s longtime research associate, Marian Gade, now of Berkeley’s Center for Studies in Higher Education, spoke of Kerr as “an intellectual, a researcher, and a writer.” She pointed to his academic output — 24 books and monographs, more than 250 chapters and articles, and some 40 reports for the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education, which he headed after leaving UC. Gade credited his productivity amid a demanding administrative career to two practices: He was tidy and well-organized (in part, she said, because he handed off piles of paper to his associates, leaving his desktop clear for the project at hand), and “when he started on a piece of writing, he knew where he wanted to end up.”

UCLA Chancellor Emeritus Charles Young and Lloyd Ulman, professor emeritus of economics and, like Kerr, former director of the Institute of Industrial Relations, also spoke at the memorial.

‘We called him Dr. Hiccup’

Kerr’s family was represented at the podium by his granddaughter, Amber Kerr (a current graduate student in the energy and resources group at Berkeley), and his son, Clark E. Kerr. Both spoke of warm moments that showed a very human side of the larger-than-life individual who made such an imprint on UC and his times. Amber Kerr in particular recalled a grandfather who could one day spark her intellectual curiosity in Greek and Roman history or stargazing, and the next day reduce his grandchildren to such gales of laughter that they called him “Dr. Hiccup.”

At the close of the ceremony, Berdahl posthumously presented the Berkeley Medal, the campus’s highest honor, to Kerr. Engraving on the medal was dated December 2003 — the chancellor said plans were in place to award the honor to Kerr at his home that month, but that Kerr’s death came only days before the scheduled presentation. Berdahl acknowledged that he couldn’t believe the medal had not been presented to Kerr years ago.

More than one speaker attempted to sum up the legacy of Clark Kerr, whose tenure with the University of California was marked by innovations, accomplishments, and controversies the like of which no UC president had ever seen. Dynes — in office only since October, yet confronted with no small number of challenges already — offered a summation as eloquent as any:

“Dr. Kerr’s contributions do not simply reside in some remote location deep in our memories,” he said. “They are around us even today — in the buildings on this beautiful campus, in the volume of research innovations that emanate from this public university, and in the hearts of students across this state who dream of going to college and creating a better future for themselves and their future families.”

The complete webcast of the event is available at webcast.berkeley.edu/events/.