Berkeleyan

Gerard Debreu dies at 83

First of four Berkeley economists to win Nobel Prize over 18-year span

![]()

| 12 January 2005

Nobel Prize winner Gerard Debreu, emeritus professor of economics and mathematics, died Dec. 31 in Paris of natural causes. He was 83.

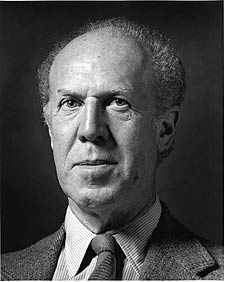

Gerard Debreu (G. Paul Bishop photo) |

A native of Calais, France, Debreu also was an officer of the French Legion of Honor and a commander of the French National Order of Merit.

Fellow Nobel laureate and Stanford University economics professor Kenneth Arrow said he and Debreu found themselves independently researching similar economic ideas in the early 1950s, which eventually led to a joint paper in 1954 on the existence of equilibrium in an economy. Arrow warmly remembered how they collaborated on the paper.

“It was a wonderful experience; he was just so brilliant to work with,” Arrow said. “One of us would say a single word, and the other would just understand immediately. I learned quite a bit from him.”

Debreu was born on July 4, 1921. He broke off his studies in mathematics as a young man to enlist in the French Army after D-Day, serving briefly in the French occupational forces in Germany until July 1945. He resumed his studies after the war, shifting his focus to economics, a subject in which he became interested after reading a book that described the mathematical theory of general economic equilibrium, established by Leon Walras in the 1870s.

“During that period, I was an Attaché de Recherches [research associate] of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, which showed an impressive tolerance for the absence of tangible results associated with the change from one field to another distant field,” Debreu dryly noted in an autobiography he prepared for the Nobel Foundation.

Prior to his almost-30-year tenure at Berkeley, Debreu worked from 1950 to 1960 at the University of Chicago and Yale University for the Cowles Commission for Research in Economics, and at Stanford’s Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences from 1960 to 1961.

Debreu joined the Berkeley faculty in 1962, at a time when the economics department was pointedly building up its staff to create a powerhouse that would soon be recognized as the pre-eminent economics department in the academic world. Debreu’s Nobel was the first in a string of four Nobel Prizes in economics won by Berkeley faculty. John Harsanyi won in 1994, Daniel McFadden in 2000, and George Akerlof in 2001.

Debreu remained an active researcher and teacher after his retirement in 1991. He was also an economic adviser to several governments and toured extensively in Europe to lecture on economic theory.

“He really was the most important contributor to the development of formal math models within economics,” said Professor Robert Anderson, who holds a joint appointment in economics and mathematics at Berkeley. “He brought to economics a mathematical rigor that had not been seen before.”

That rigor made lasting changes to the field of economics, making it a more formal and precise science, Anderson said.

Debreu is remembered by friends as unfailingly polite and gracious, with a love of hiking in the Bay Area and of good food and accommodations when traveling. He also took an interest in politics, deciding to become an American citizen after the Watergate hearings were over and he saw how the country had dealt with the constitutional crisis, friends said.

“After the impeachment, he said: ‘This is a great country. I will become a citizen,’” Arrow recalled. Debreu became a U.S. citizen in July 1975.

Arrow said Debreu also showed great courage when he went to Chile around 1980 on a human-rights fact-finding mission on behalf of the National Academy of Sciences to report on how scientists were being treated.

It was a more playful Debreu who was seen on campus in 1983, just before he won the Nobel, when he enthusiastically volunteered to coach the first-ever “Little Big Game” between economics graduate students from Berkeley and Stanford — despite knowing nothing about American football. Debreu coached the Berkeley team while Arrow coached the Stanford team. The intradepartmental touch-football game became an annual event, with the winner awarded a bronzed-apple-core trophy in honor of Arrow’s and Debreu’s Nobel Prize-winning theoretical work on the equilibrium (or “core”) of an economy.

“Everything he did was with elegance,” Anderson said. “In his lectures he would always make a beautiful presentation, which clearly identified all of the assumptions and explained the proof in detail — and then ended precisely when it was supposed to.”

Debreu is survived by his former wife, Francoise Debreu; two daughters, Chantal De Soto and Florence Tetrault; five grandchildren, and four great-grandchildren. A service at the Columbarium of the Pere Lachaise Cemetery in Paris was held on Friday, Jan. 7.