Berkeleyan

|

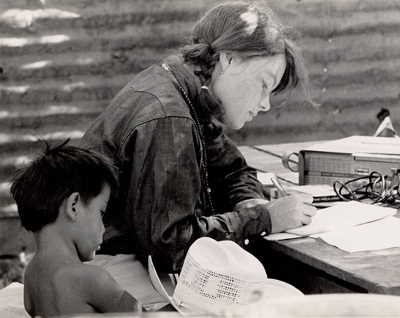

Hinton as a Berkeley undergrad, circa 1965, with an unidentified friend and a state-of-the art Uher portable reel-to-reel tape recorder in Supai, Ariz. Because the village had no electricity at the time, she recharged the machine's batteries with the help of a generator turned on briefly each evening. (Matt Hinton photo) |

Keeping Native tongues out of the pickling jar

After decades devoted to breathing life into dying California languages, linguist Leanne Hinton views her profession's value as far more than academic

![]()

| 07 March 2007

Leanne Hinton first heard the faint cry of dying languages at the bottom of Havasu Canyon, a 3,000-foot-deep cut in the Colorado Plateau beloved by backpackers for its clear, towering waterfalls. A remote branch of the Grand Canyon reachable only by foot, helicopter, or pack animal, this ancient chasm is home to the 650-member Havasupai tribe, which has inhabited the village of Supai for eight centuries. When Hinton, then a Berkeley undergrad, hiked the eight-mile trail down to the village in the summer of 1964, the Havasupais had no system of written language.

Hinton was instrumental in changing that. And that summer in Supai changed her as well, planting the seeds of a career - and a calling - as a champion of vanishing Indian languages, working closely with tribal members throughout California to combat further erosion of the state's ever-dwindling language diversity. As part of Berkeley's linguistics faculty since 1978, including three years as department chair, she has made it her mission - through both her writings and her hands-on language conferences and workshops - to keep the fires of Native languages burning.

"When we lose languages we're losing knowledge," says the soft-spoken Hinton, who estimates that of the more than 100 languages indigenous to what is now California, only half still have living speakers. "We're losing not just a set of words or a grammar - and of course that's very important to linguists - but, more broadly, we're losing whole philosophical systems, oral-literature systems, ceremonial systems, and social systems along with the language. So language is one of an array of cultural phenomena that are going away."

For Hinton, however, the wider impacts of such losses are secondary to the toll on - and the inspiration of - the people whose ancestors were fluent in Karuk, Miwok, Mutsun, and scores of languages and dialects that today have only a few, if any, remaining speakers.

"I'm really involved in this because of the passion of the people in these communities who are losing languages," explains Hinton, who last year received a Cultural Freedom Award from the Lannan Foundation. "The important thing about language survival is that people see it as a part of their human rights. And it is. People have the right to retain their language, and have a right to retain their culture if that's what they want to do."

An accidental linguist

Longtime linguistics-faculty member Leanne Hinton in her Dwinelle Hall office. (Peg Skorpinski photo) |

Growing up in La Jolla, Hinton never expected to make a career of preserving and resurrecting moribund languages, or even - as was customary then in linguistics - merely documenting them. "My own journey to the languages of California has been long and full of detours," she wrote in the introduction to her 1994 book Flutes of Fire. The journey began, fittingly, in Arizona, with a language, Havasupai, that is relatively robust.

Hinton traveled to Supai not as a linguist but as a budding ethnomusicologist. Her father, a retired marine biologist, is the renowned folk musician Sam Hinton, and she herself studied folk and ethnic music well into grad school. Her change in direction was set when she told her academic adviser, the late Berkeley folklorist Alan Dundes, that she hoped to do field work somewhere within driving distance over the summer break.

"He just said right out, 'Well, the Havasupais might be an interesting place to go, no one's really studied their music,'" she recalls.

What the 22-year-old undergrad found - beyond new friends and a culture that took her in and reshaped her outlook - was that "sung and spoken language were very different from each other," a discovery that fascinated her and became the basis of a course she would later teach at Berkeley. "There were all kinds of very interesting things going on in the texts of the music," such as the use of archaic words and non-word sounds that nonetheless conveyed meaning. "I was very interested in this whole notion of meaning versus words," she says. "What really got me into linguistics was my interest in that aspect of ethnomusicology."

Hinton eventually went on to earn her Ph.D. in linguistics at UC San Diego, and soon accepted a teaching job with the University of Texas. The Havasupais, meanwhile - for whom she'd been writing a monthly newspaper column on "how to write your language" since her grad-school days - asked her to head up their fledgling bilingual-education program. She accepted, making the 900-mile trip to Supai from Dallas every two weeks.

The experience was an eye-opener for Hinton. Havasupai "is not what we call a moribund language, because kids are still learning it," she explains, pronouncing it "a little bit endangered." But tribal leaders, worried by the growing encroachment of English on their ancestral tongue, viewed the burgeoning bilingual-ed movement of the 1970s as a model they could apply successfully in their own schools. Many other North American tribes, says Hinton, were also creating programs to teach a range of subjects in students' Indian languages.

"They saw bilingual education as a way to turn around the process of language decline they had been going through, and that had started, of course, with the schools," she says. "They had gone through this long period of boarding-school education, where the languages were absolutely not allowed in the schools and weren't allowed on the playgrounds, or in the dorms, or anywhere, as a way to try to actually kill off the languages and have everybody become monolingual English speakers.

"So this was an opportunity, all of a sudden, for the languages to come back to school, and to regain some of the respect from tribal members that they had lost," she says. That, however, required a standardized writing system, something most Western tribes didn't have. Hinton worked with the tribe to develop one, and in 1984 published the first Havasupai dictionary.

Yet even though children could speak Havasupai - "one of only 20 [Native] languages in North America that kids are still learning at home," Hinton says - she detected some problems. The most serious was the lack of immersion in the second language, with teachers and students alike constantly slipping back into English.

"Even with Havasupais, where everyone knew the language, teachers would start out in English, saying, 'Okay, kids, today we're going to talk about the colors in Havasupai,'" she says. "Teachers would tell me, 'When I write Havasupai I think in English, and translate.' Because writing itself was sort of this English thing that you do, and it was hard to transfer."

"It got me very interested in the whole idea of immersion as a language-teaching method and as a way of interacting," Hinton adds. By the early 1980s - by which time she was an assistant professor of linguistics at Berkeley, and accepting invitations from California tribes to speak on the topic of teaching language - the technique was of far more than mere academic interest.

Speaking equals success

In addition to leading language workshops with a focus on immersion, Hinton began writing a monthly column for News From Native California, a journal started by Berkeley publisher Malcolm Margolin. (She retired the column after 10 years, collecting some of the essays in edited form in Flutes of Fire.) In 1992 she joined Margolin and Tongva/Ajachemem artist and tribal activist L. Frank Manriquez in putting together a major conference on how to save Indian languages, an event she views as a watershed.

"It was a very historic conference," she says. "Before that, everybody was doing their own separate things, and feeling pretty lonesome. And all of a sudden they were with other people who shared the same interests. It was a tremendously positive, emotional gathering."

The conference gave birth to a group called Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival (AICLS), with Hinton as a founding board member. The nonprofit now runs a number of programs aimed at putting into practice an essential key to language survival, but which Hinton says came as something of a surprise: the need for new speakers of the old languages.

"To a linguist this was a real learning experience, because when linguists say, 'Oh, we've got to save these languages,' they often mean 'let's document them,'" observes Hinton. And while she agrees that documentation is "exceedingly important," it's not enough to save a language. "A lot of people were saying that 'documenting the language is pickling the language - we don't want documentation, we want new speakers, and that's what we want to focus on.'"

And that, in fact, is where Hinton has focused much of her own energy - that is, when she isn't teaching Berkeley students, directing the Survey for California and Other Indian Languages, curating the sound collections at the Hearst Museum and the Berkeley Language Center, conducting linguistics research, or writing books and articles. (In addition to works of scholarship, her eight published books include How to Keep Your Language Alive, a handbook for one-on-one teaching of endangered languages, and a children's book, Ishi's Tale of Lizard, a 1993 nominee for a PEN Center USA West Literary Award.)

Under the auspices of AICLS, Hinton oversees weeklong "Breath of Life" workshops on campus every other summer - "I had originally called it the Lonely Hearts Language Club," she laughs, "but I was overruled" - at which tribal members gather to learn new techniques for learning, teaching, researching, and preserving languages that have no speakers. She also created the Master-Apprentice Program, which pairs an elder speaker with a younger tribal member who wishes to learn the language.

And whether or not a particular language still has a living speaker, Hinton makes sure those interested in endangered languages are able to take full advantage of Berkeley's archives, which she says "represent one of the largest collection of documents on California Indian languages in the world, maybe the biggest."

"One of the most important things people learn is that they can come back here anytime," she says. "A lot of people say they were terrified of Berkeley, that they would never have come on their own. That they are actually allowed to go into a library or an archive and study the materials is something they had no idea about."

Such efforts, Hinton believes, are paying off.

"I think what constitutes success is people using the language," she explains. "And what I see is that people are. Any word they know, they're figuring out places where they can use it every day - tribal councils saying, 'Okay, you have to vote yes or no in our language, even if those are the only two words we know.' People are developing their own archives and libraries with copies of all the materials on the language. People are developing curriculum materials, dictionaries, phrase books. And so what's happening is that the languages are coming into use again."

As a preface to Flutes of Fire, Hinton offers up a Maidu tale that explains the origin of Indian languages and provides the book's title. Mouse, the story goes, was sitting atop the assembly house, "playing his flutes and dropping coals through the smokehole," when Coyote interrupted him. As a consequence, only people in the middle of the house received fire; today, when the others talk, "their teeth chatter with the cold." The reason Indians have so many different languages, the tale concludes, is that "all did not receive an equal share of fire."

For many, the fire is in danger of going out. Hinton - who still, four decades after her first visit to Supai, finds it "much more satisfying to be using my linguistic knowledge for some kind of real-world benefit, rather than just writing for other linguists" - is doing her best to fan the flames.

Additional information:

- A faith in words - Berkeley linguists are helping California tribes work against time and the odds to revive their dying languages

- Native tongues - one of the 25 brilliant California ideas featured in California magazine