Berkeleyan

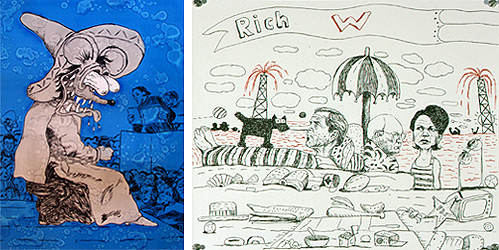

Above left, Those Specks of Dust (2006). Above right, in Poor George (After Philip Guston) #7 (2004), Chagoya updates Guston's 1971 caricatures of Richard Nixon. "I found a lot of parallels in the Bush and Nixon administrations," notes the artist. |

Rewriting history and poking fun at the powers that be

BAM/PFA opens a 25-year retrospective of Enrique Chagoya's audacious artwork

![]()

| 06 February 2008

Chagoya at BAM/PFA |

Mexican-born artist Enrique Chagoya deliberately mixes diverse and often opposing elements in his art. Superman keeps company with an ancient Aztec god. Jesus pilots a military helicopter whose progress is slowed by Alice in Wonderland. On Wednesday, Feb. 13, "Enrique Chagoya: Borderlandia," a 25-year survey of the artist's work that showcases his wide-ranging palette, will open at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive.

Chagoya, 55, who lives in San Francisco, grew up in Mexico City with a wealth of cross-cultural influences. He immersed himself in pop culture from both sides of the border, including Spanish translations of North American TV shows ranging from The Lone Ranger to I Love Lucy to The Twilight Zone. And like many boys, the draw of comic books - both American and Mexican - proved irresistible to him.

Other indelible influences: Pre-Columbian culture came alive in the sound of Nahuatl, the Aztec language, while even as a boy he could feel the power of the past in the baroque art within Mexican Catholic churches, which were constructed with stones from the pyramids. "These churches have this energy that's difficult to describe. In some of them, there's no inch that's not decorated with painting, gold leaf, or sculpture," notes Chagoya.

While young Chagoya was exposed to art and ancient ruins, he also received lessons in injustice. As a high-school student he experienced government-sanctioned violence when the Halcones (falcons), a paramilitary squad, attacked a peaceful demonstration in which he was participating and killed 100 people. "I had to run for my life. Right in front of me Halcones were hitting people with bamboo sticks that had knives attached to them," he recalls. The incident, which was reported as a fight between warring student groups, was "a lesson in how media and politics work," observes Chagoya.

Such occurrences and other dispiriting chapters in Mexico's history informed Chagoya's social conscience. As a teenager he came upon a book of paintings and drawings by Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828) that offered him ideas on how to channel his political critiques. Years later, in his series "Homage to Goya," he made "forgeries" of the great artist's 19th-century "Disasters of War" etchings. These works, he explains, were intended to explore how the Spanish political artist would have portrayed modern-day events.

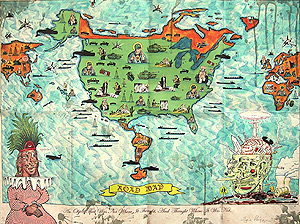

Road Map (2003), painted as the U.S. prepared to invade Iraq, symbolizes "the expansionist ideology of this administration," explains Chagoya. The rest of the world has shrunk, so that the U.S. dominates the picture. |

Chagoya employs social satire and something he's dubbed "reverse anthropology" in his work. Those Specks of Dust, an example of the former, references Goya's style and also that of '60s artist and cartoonist Ed "Big Daddy" Roth. Goya's original etching was set during the Holy Inquisition and depicted a prisoner on trial awaiting execution. In Chagoya's version, hot-rod icon Rat Fink is on the hot seat, an "illegal alien" awaiting a verdict. Chagoya likens the climate during the Holy Inquisition to that of today in which ultra-nationalistic politicians have created unflattering stereotypes of undocumented workers, fanning anti-immigrant sentiment in the process.

Chagoya started drawing cartoons when he lived in Mexico (he moved to the U.S. in 1979 with his then-wife). He cartooned for union and student newspapers, but long before that he drew cartoon characters as a boy. "I used to draw my teachers naked," he says. "I have a cartoonist's mind. Most of the time I don't try to convince people about any idea. I have thoughts I have to express somewhere, and sometimes they make me laugh. That's when I know I have to do something with them."

Crossing I (1994) hints at the range of Enrique Chagoya's diverse influences. |

While Chagoya satirizes the powers that be in his works of social conscience, his reverse-anthropology pieces offer his alternate vision of history. In a panel from the codex (an accordion-style, sometimes two-sided, amate-paper book) Tales From the Conquest, Chagoya recreates Pablo Picasso's famous work Les Demoiselles d'Avignon so that two of the women's faces are painted to look like African masks.

Early-20th-century artists like Picasso appropriated art from Africa, Asia, or Native America to create something "modern" without adequately acknowledging or understanding the culture, charges Chagoya. Likewise, Henry Moore used Aztec sculpture to develop some of his seated figures, and Frank Lloyd Wright borrowed from Mayan architecture to design some of his Los Angeles buildings.

"What if a Native American had discovered European art and decided to use that in a Native American-style piece," he muses. "If the Aztecs had conquered Europe, you would begin to see pyramids everywhere." Such an idea inspired Chagoya, who found old, partly ruined biographies of European artists in a Mexican flea market, to paint over the usable pages. "How would it be if someone imposed their own culture on your culture?" ponders the artist.

Chagoya's codices pay homage to ancient Aztec and Mayan codices. After their 16th- century conquest of Mexico, Spanish priests and military burned nearly all of these books, effectively destroying the history of the indigenous people. The books covered subjects as diverse as astronomy, medicinal herbs, calendar cycles, history, and religious rites and rituals, and the invaders saw them as a pagan threat. Upon learning of the destruction, many indigenous people committed suicide.

"Those who win the wars write their version of events," reflects Chagoya. "Not only history, but the culture gets transformed by those who win the wars."