Berkeleyan

|

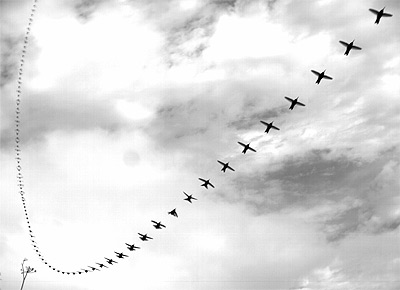

A male Anna's hummingbird during a display dive, compiled from high-speed video. At the bottom of the dive, the bird flares its tail for 60 milliseconds. The inner vanes of its two outer tail feathers vibrate in the 50 mph airstream to produce a brief chirp. (Christopher J. Clark & Teresa Feo/UC Berkeley photo) |

Anna's hummingbird chirps with its tail

What sets the tone for hummer romance? A high climb, a steep dive - and just the right vibration

![]()

| 06 February 2008

The apparent vocalizations - beeps, chirps, and whistles - made by some hummingbirds are actually created by the birds' tail feathers, according to a study by two Berkeley students. Using a high-speed camera, they recorded the dive-bomber display of the Anna's hummingbird (Calypte anna), the West Coast's most common hummer, now in the heat of mating season. The video established that the chirp a male makes at the nadir of his dive coincides with a 60-millisecond spreading of his tail feathers - faster than the blink of an eye.

Wind-tunnel tests confirmed that the outer tail feathers vibrate like a reed in a clarinet. The bird's split-second tail spread at dive speed thus produces a loud, brief burst that sounds like a chirp or beep.

"This is a new mechanism for sound production in birds," says lead author Christopher Clark, a graduate student in the Department of Integrative Biology. "The Anna's hummingbird is the only hummingbird for which we know all the details, but there are a number of other species with similarly shaped tail feathers that may use their tail morphology to produce sounds."

The most likely birds to make tail-feather chirps are the Anna's relatives, the "bee" hummingbirds, which are the tiniest hummers in the world. They include the ruby-throated and black-chinned hummingbirds that migrate between the eastern United States and Central America, the Allen's and Costa's hummingbirds that, like the Anna's, reside year-round in the western U.S., the widespread Rufous hummingbird that migrates between the United States and Central America, and the tropical woodstar hummingbirds.

"Most have funny tail feathers with tapered or narrow tips, all have mating dives, and all make a different sound," says Clark. "It's possible that sexual preference by females has caused the shape of the tail feathers, and thus the sound, to diverge, thereby driving the evolution of new species."

"This phenomenon nicely illustrates the strength of the evolutionary process, and sexual selection in particular, to derive novel functions from pre-existing structures," notes Robert Dudley, a professor of integrative biology who is Clark's adviser.

The tail-feather beep of the Anna's hummingbird is similar to the whistling feathers of ducks and other birds, including the mourning dove, the whistling swan, and nighthawks. Those sounds, however, seem to be incidental to wing flapping, the researchers said.

The tail-feather beep of the Anna's hummingbird, on the other hand, is an important part of the dive display that seduces females and also serves to drive away rivals or other threatening animals.

Nevertheless, Clark says, the reed-like mode of sound production may explain other bird-feather "sonations." For example, while researchers have found tail feathers to be the source of winnowing sounds made by snipe, an elusive member of the sandpiper family, the mechanism is unknown.

Dramatic display

The display of the male Anna's hummingbird, a green-backed hummingbird with a green head and red throat that weighs less than a nickel, is highly dramatic. During the breeding season, which lasts from November through May, males ascend rapidly to a height of 100 feet or more, then execute a looping dive at speeds of over 23 meters per second (50 miles per hour), Clark and his co-author, recent Berkeley graduate Teresa Feo, calculated from their video. When they reach the bottom of their dive and round upward near a perching female or intruder, the birds produce a loud chirp.

Ornithologists have long debated whether this sound is produced vocally or by the tail. To determine the origin once and for all, Clark and Feo observed for two springs the mating flights of male Anna's hummingbirds at the Albany Bulb, a shoreline park near Golden Gate Fields. With a borrowed high-speed camera taking 500 shots per second, they recorded male display dives performed for the benefit of a caged female (or, on occasion, a stuffed female hummingbird attached to a low bush). The video revealed a very brief flaring of the tail feathers at the bottom of the dive, just prior to the bird's ascent for another dive. The flaring coincided with the chirps.

To confirm, the students captured males and plucked or trimmed their tail feathers, knowing that birds can fly without tail feathers and that they typically grow back in five weeks. Those males missing the outer pair of five pairs of tail feathers, or those with the trailing (inner) vanes of the outer feathers trimmed, were unable to make dive sounds.

The researchers then took the tail feathers to a wind tunnel at Stanford University's Hopkins Marine Station in Pacific Grove and demonstrated that a wind blowing at the same speed as a diving hummingbird made the tail feathers flutter at a frequency of 3.3-4.7 kilohertz, equivalent to the highest note on a piano, four octaves above middle C. High-speed video showed the sound was produced by the fluttering of the trailing edge of the outer tail feathers; outer tail feathers missing the inner vane produced no sound. Apparently, barbules linking the barbs of the feather vane make the vane stiff enough to vibrate like a reed in a wind instrument.

"Just blowing outward on the tail feather makes the same frequency as in the dive," says Feo, who plays clarinet in the Cal Band.

Clark and Feo, both with the campus Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, hope to test related hummingbirds to see whether their tail feathers also vibrate and are responsible for chirps made during display dives.

To hear a recording of an Anna's humingbird's chirp, and to view a video of a male's display dive (slowed down to show the brief flare of its tail feathers), visit newscenter.berkeley.edu/goto/hummingbird.