UC Berkeley Web Feature

|

A

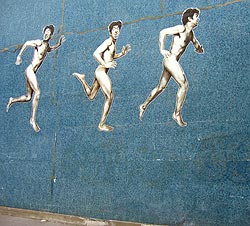

detailed view of one of the walls by Jean Faucheur's

atelier, onto which a poster has been glued.

(Photos by Gene Tempest except where noted) |

From Paris: An interview, the last café, and farewells

| About Student Journal 2006 [an error occurred while processing this directive] |

PARIS - Jean Faucheur met me at 9:30 a.m. on a Thursday in blue, Chinese-inspired pajamas that probably should have been silk, but instead were of that stiff, harsh material, which, if you're lucky, will be cast into a martial-arts costume and not your pajamas.

They — Jean's pajamas — had sad, mournful knots of fabric for buttons. I sat to his left at a table in the shade while he talked to sociologist Alain Milon about urban art and smoked from a bandaged pipe. I thought: How grand! that he had worn pajamas to our interview; it was too bad that they were not of silk.

Jean was not formally a part of my project on the posters of mai '68 — he was much too young to have participated, he reminded me, stressing the word "young" — jeune — and citing his "good looks" as proof. (For a primer on Mai '68, read the last dispatch.)

My relationship to him was not unlike that of a passerby to the ever-central Clarissa Dalloway in Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway. Perhaps, because he is an artist (and the world turns around artists, like little Louis XIVs, like small suns), it seemed natural that I should sit next to him, quiet, timid, and still puffy with sleep. Maybe, to Parisian artists at 9:30 a.m. on a Thursday, life is an eponymous novel.

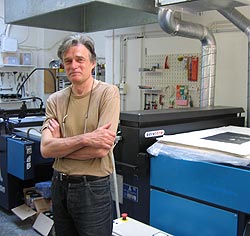

Interviewee Eric Seydoux today owns a silk screening workshop. Much more modern than the Atelier Populaire, it runs on machines; Seydoux can print onto almost any kind of media, including glass, wood, and textiles. |

|

The canal St. Martin in northeast Paris is a popular place for street art. Probably silk screened, these images have been wheat-pasted to the wall. |

|

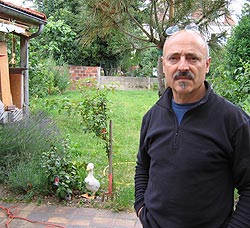

Interviewee François Miehe, who now teaches at the Arts-déco, where he was a student in 1968. |

|

"Are you going to get your baccalaureate or what?" French artists maintain that 'pochoir' (stenciling) is a French-only technique, but it can also be spotted in Berkeley and elsewhere. |

|

Street artist Atlas, a friend of Faucheur's, studied Arabic and uses it in his graffiti. |

|

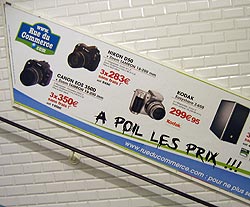

Advertising companies have begun to use graffiti — because it's hip — to sell their products. Here, a fake graffito has been digitally added to an ad for digital cameras. |

In fact, I was meeting with Jean and Alain — it is quite curious to call them by their first names — Monsieur Faucheur and Professeur Milon, rather, for another project: Professor Ann Smock's conference on the "Poetry of the Every day," to be held in Berkeley on October 14 and 15. Professeur Milon will be at the conference to speak about graffiti and street art.

Monsieur Faucheur, I learned, was a leader of a militant artistic group that worked at La Place Sans Nom — "the square without a name" — in 2001. Faucheur called it "an open-air gallery" (une galerie à ciel ouvert), literally "an open-sky gallery."

Faucheur, like my subjects for my thesis interviews, has worked extensively with posters. At La Place Sans Nom, there were two large, horizontal advertising boards. Every Thursday night the colleurs — Paris's advertisement gluers — paste the week's new publicités onto boards all over the city. Every Friday night, Faucheur and his friends had beers at the café on the square and posted their art over the ads.

Theirs was not spontaneous, wild-cat gluing, of course. Faucheur had taken the dimensions of the boards, and prepared his pieces to fill the space exactly. During the week, he would paint his designs onto paper, divide the paper canvas into sections, cut them, and then roll them up. The rolls were numbered, and Friday night Faucheur and his friends had only to glue. They used flat-headed brooms and plastic buckets of glue.

* * *

I lived in Paris six weeks this summer, and in the end I did seven interviews (I cannot count my morning with Faucheur as anything but a pleasure). When the NewsCenter editor first discussed the parameters of this series of dispatches with me, she wrote, "I can see it as a three-parter," the third part of which would be "conclusions that you might not have yet."

What conclusions do I have now? I wondered when I first read her e-mail.

When I listen to radio interviews, and sometimes, like today, when I listen to the ones I recorded this summer, I notice that a good — or clever — interviewee hears the question he wants to answer.

What conclusions do I have now? I mumbled as I thumbed through A Moveable Feast for inspiration. Hemingway wrote, "In Paris, then, you could live very well on almost nothing and by skipping meals occasionally and never buying any new clothes."

This is true. But in Paris, now, if you are going to eat out, eat out for lunch; a lunch menu is less expensive than dinner's. If you are going to have coffee, have it at the counter; it is usually 30 centimes less, and you can read the paper, too.

What conclusions do I have now? I asked myself in a café at the Place de la République, three days before my departure from Paris. It was a Saturday, and I was early for an interview — my last interview.

The café was full. It was a small place and seemed removed from the boulevard even though it wasn't, really. There were three men at the bar; they were the morning's — every morning's — regulars. One had an espresso. One had a cigarette. One had a newspaper. The best of the French '80s was on the radio, which was turned down low, but the regulars still shouted a little, as though they'd just attended a loud concert and their ears remained full.

I ordered a cup of coffee from the man behind the bar. He was old and birdlike — all bones with skin stretched over. His name was Robert. The regular with the paper said to no one in particular, "Robert, il sera jamais en retraite. C'est comme Zizou." ("Robert is never going to retire. He is like Zinadine Zidane —the French soccer captain.") Robert was eating pâté, bread, and pickles, even though it was only 11 a.m.

He stood there looking like some terrible, sympathetic egret, eating pâté next to signs that read: "obituary note: credit is dead," and "we no longer accept checks, or credit cards." These were signed "la Direction." I wondered if "the Direction" was Robert.

A girl came in and dropped off her apartment keys. It was vacances — vacation — time. Paris would be empty by the end of the week. Robert took the keys, and the girl said, "I will see you in September."

* * *

I rode away from Paris facing backwards in a scratchy seat on the B line of the RER. Marcel Pagnol, the famous French filmmaker, also wrote books about his childhood. These were made into movies by some lesser-known director, but they remain good — great, even —sentimental films about youth.

Marcel rides away from his summer house in the hills facing backwards in a horse-drawn car. He is a little boy and cries because vacation is over. He cries because he has to leave his summer home. To ride away from Paris in a seat that faces backwards on the RER B line is like being dragged away from the hills of one's youth. One does not want to go. It is as though you are riding toward the future despite yourself. And, moving forward, you can only look back.

But perhaps that is like the study of history after all: riding forward accidentally, looking backward all the time.