UC Berkeley Web Feature

|

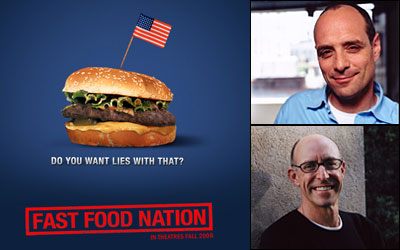

The preview screening of "Fast

Food Nation" included a discussion by investigative reporter and film cowriter

Eric Schlosser (top right) and UC Berkeley

journalism professor Michael Pollan. (Credits) |

"Dark times": Eric Schlosser, Michael Pollan discuss a nation of fast food, cheap labor, and profit-driven compromises

BERKELEY – When is a hamburger just lunch?

Never, if you're Eric Schlosser or Michael Pollan. For these two investigative journalists — the de-facto rock stars of the food-politics movement — that piece of meat is a microcosm for serious problems plaguing this nation in public health, the environment, animal welfare, labor, immigration, and more.

Schlosser was on campus Wednesday night (Oct. 18) to promote a sneak preview of director Richard Linklater's newest film, "Fast Food Nation," a dramatic adaptation of Schlosser's 2001 best-selling, nonfiction exposé that they wrote together. (The film opens in Australia next week and in America in mid-November.) Pollan, who teaches journalism at UC Berkeley and is the author of this year's chart-topping dietgeist work, "The Omnivore's Dilemma," joined him for a post-screening chat about the state of food production in this country.

Promoted by e-mail and word of mouth, the event attracted a long line of would-be audience members to Wheeler Hall. The crowd thinned out a bit when those waiting learned they would have to check any video-capable cell phones with security guards at the studio's request.

Most stayed, however. Among the audience was Ignacio Chapela, an associate professor of Environmental Science, Policy and Management at UC Berkeley who's well known to food politicos for his screen time in "The Future of Food," a documentary about genetically modified crops. Chapela was there to support what he calls a new chapter in a story about the role of food that's been evolving over the past few decades.

"This used to be such a weird little niche," Chapela said of the movement before the movie started. "But it's no longer fringe at all. I think everybody across the nation is very interested in food right now, mostly from a nutrition and health standpoint — not yet for environmental reasons."

Darkness visible

Schlosser told the audience before rolling "Fast Food Nation" that it was not a documentary, comedy, or satire, and not to expect a literal adaptation of his work. "I should warn you, this is a very dark film," he concluded. "But these are very dark times."

He wasn't kidding. Although many of the film's scenes take place in a pitilessly lit fast-food restaurant and slaughterhouse — the fictional Mickey's Burgers and its supplier, Uniglobe Meat Packing, respectively — the tone and humor are defiantly black. The elliptical story line is set in motion by a naïve Mickey's executive (Greg Kinnear) who is sent to a small town in Colorado to investigate why "fecal coliform levels are off the charts" in tests of uncooked patties of the Big One, the company's flagship burger.

"I don't understand," he tells his boss.

The explanation: "There's s*** in the meat."

| 'We

wanted to show how very nice people become complicit

in things that aren't nice at all. The goal is to

unsettle, provoke, make people think and feel.' -Eric Schlosser,

"Fast Food Nation" |

Excrement, both literal and figurative, is a recurring theme in this loosely organized, ensemble-driven piece: Illegal immigrants from Mexico hose it off the slaughterhouse kill-room floor, Mickey's teenage employees put up with it, and a hapless group of college students attempting to liberate cattle from a feedlot step in it.

A close-to-final scene in the slaughterhouse, which incorporated actual footage of cattle being killed, skinned, and dismembered, was enough to send several audience members fleeing from the auditorium. The rest applauded as the credits rolled.

The way of all flesh

After the film, Schlosser and Pollan — who rather resemble each other, like two beaky, sports-jacketed herons — took the stage for a post-screening discussion.

"I didn't have dinner, but I am so not hungry right now," Pollan said, referring to the graphic footage.

Schlosser was unapologetic. "If you're going to eat meat, that's how it is."

He had been reluctant to take on the original Rolling Stone magazine assignment that had turned into "Fast Food Nation" the book, he said, because "I ate a lot of fast food then, and I liked it." Only elitists and food snobs would criticize Whoppers and Big Macs, he thought. However, the more he tried to find about the fast-food industry, the more he "became intrigued with this world that was deliberately being hidden."

As many have done before him, Pollan compared "Fast Food Nation" to Upton Sinclair's 1906 classic of investigative journalism "The Jungle." Both Sinclair's and Schlosser's books "aimed at America's heart and hit its stomach," as Sinclair famously said of his own, focusing on the food industry's dependence on an easily exploited, unskilled immigrant labor force and its acceptance of a certain amount of contaminants in meat as a cost tradeoff. Schlosser confirmed that "The Jungle" indeed had been a literary touchstone for him, along with Sherwood Anderson's "Winesburg, Ohio" and John Dos Passos's U.S.A. trilogy.

After a few minutes, Pollan opened up the discussion to the audience. A student asked which was more likely to effect real change in the industry: personal eating choices or government regulation.

"The government isn't going to take any steps unless people make it known that they want things to change," said Schlosser.

Rage against the machine

Another asked whether in his many interviews he had met fast-food executives like the character played by Greg Kinnear — essentially decent, average people, with families and consciences. He'd met many, Schlosser said, and "I've tried not to demonize any of these individuals. The problems are these systems. They're bigger than any one individual."

Fast-food and meatpacking industry executives are cogs in the machine of corporate profits, just like their workers — only with more money, and thus more to lose, said Schlosser. There are no villains whose removal would solve everything, Schlosser argued. "We wanted to show how very nice people become complicit in things that aren't nice at all. The goal is to unsettle, provoke, make people think and feel."

He succeeded in doing so with at least two audience members — Karina Schell, a third-year conservation and resources major at UC Berkeley, and her friend Ian Thomas, a senior at San Francisco State University. Neither student eats fast food from the biggest chains; Thomas admitted he occasionally still patronizes smaller ones like In-N-Out Burger.

Schell, a vegetarian, said she had read part of "Fast Food Nation" already because she is very interested in food politics, an interest that Wednesday's event had only strengthened.

"I think Schlosser raised some important issues — it's not just food, it's the systems we're embedded in," she said. "We have to increase awareness and ask questions about where our food really comes from."

Credits: "Fast Food Nation" poster courtesy of Fox Searchlight Pictures and Participant Productions; Schlosser photo by Mark Mann; Pollan photo by Ken Light.