UC Berkeley Web Feature

|

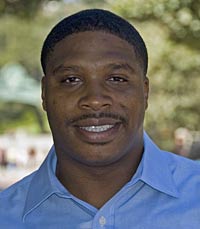

Being welcomed to UC Berkeley as a junior transfer student was beyond Derick Brown's wildest dreams when he was growing up in San Francisco's poverty- and crime-ridden Western Addition. (Steve McConnell / NewsCenter photos) |

Former street tough takes miraculous route to UC Berkeley

BERKELEY – Next week, Derick Brown starts his junior year at UC Berkeley, arriving as a transfer student from City College of San Francisco. While the campus is less than 15 miles from the Western Addition neighborhood where he grew up, it may as well be the moon, as far as many of his former cohorts are concerned.

"Growing up, Berkeley was just off limits. African Americans where I come from, we just can't get in," he said. "But I took a chance and enrolled in community college, then things started happening, and look at me now. I'm floating on a cloud."

Anne De Luca, UC Berkeley's deputy director of undergraduate admissions, can attest to that: "He's just a great success story," she said.

'Growing up, Berkeley was just off limits. African Americans where I come from, we just can't get in. But I took a chance and enrolled in community college, then things started happening, and look at me now. I'm floating on a cloud.' -Derick Brown |

Brown, 28, is among 2,100 students who are transferring this fall to UC Berkeley from community colleges around California. At least one in three of these students has had to overcome poverty or language obstacles and is frequently the first in his or her family to attend a four-year college.

Brown certainly fits the profile.

Born in San Francisco in 1979, Brown was the eldest of fraternal twins. His mother raised her three boys (she bore another son in 1984), eking out a living on welfare while the children's father made "guest appearances," Brown said. They lived in crime-ridden public housing in the Western Addition, where being street-smart got you a lot more respect than being book-smart, he said.

"For us, school was never pushed. Just graduating from high school was an accomplishment," Brown said.

But right from the get-go, Brown wanted more out of life. "I used to say to myself, 'This can't be all there is,'" he recalled.

A young entrepreneur, Brown offered to help neighbors with jobs in exchange for the odd dime or quarter. He took out the garbage, went on grocery store errands and moved furniture.

He channeled his youthful energy into the Ernest Ingold Clubhouse, a branch of the Boys & Girls Clubs of San Francisco that serves the Western Addition. There he would play ball with his friends and get involved in healthy activities. "I went there any chance I could," he said.

By the time he turned 13, though, the club had little to offer teenagers, and Brown began to drift. By 15, he was hanging out with drug dealers and gang members on street corners. He says he served a short stint in juvenile hall in connection with a robbery committed by some of his peers.

At the time, Western Addition gang members were feuding with gangs from the Sunnydale housing project in the Ingleside district. This frequently led to shootouts at the projects. "It was like the wild, wild West," Brown said. The violence finally spurred Brown's mother to move her family to Hayward. But it was too late. Her twin boys didn't want to leave the Western Addition, and soon returned.

"That was the low point," said Brown, looking back. "My life could have gone either way."

After barely graduating from George Washington High School, Brown got a clerical job at a travel agency. But after a year, he lost interest and decided to work for the Ernest Ingold Clubhouse. He figured he'd be a shoo-in for a job there as teen director, but he didn't have enough experience, so the employer offered him a job as social recreation director for the Sunnydale housing project, the territory of his former rivals. "I said, 'I can't work there. That's crazy,'" said Brown.

Nonetheless, he drove to Sunnydale, saw young kids with nothing to do, and decided to give the job a shot. He took the children to basketball games and on field trips, and won their respect. Less than a year later, he learned that the person hired as teen director at the Ernest Ingold Clubhouse had quit. Did Brown want the job? the clubhouse asked. He sure did.

Brown hit the ground running and designed a comprehensive program that boosted the number of teenage participants from a handful to around 80. He pulled together a basketball league, teen leadership and career preparation programs, arts and crafts workshops and a technology center.

"He's really shown that he's a strong role model, not only for the youth but for the community as a whole," said Jennifer Dominguez, director of the Ernest Ingold Clubhouse. "I don't know anyone from the community that's gone on and achieved what he has."

Meanwhile, he started volunteering as a counselor with the San Francisco Juvenile Probation Department, telling his life story to foolhardy young boys and girls. "We had 13-year-olds, 14-year-olds coming in for murder," he said. "They were just little kids, misguided little boys. They had potential, but their home environment wasn't good. All they knew was how to hustle. I understand that. I've done that. It's another world out there."

Brown encouraged his young charges to pursue an education, but he was at a loss to explain his own lack thereof. And so in 2004, when he saw a poster that said "City College of San Francisco: Enroll Now!" while waiting for the bus, he decided it was time to return to school. At the very least, it would improve his chances of getting a paying counseling job with the probation department's Juvenile Justice Center.

He aced his first two years at City College, and landed a counseling position with the Juvenile Justice Center. "Because of his positive outlook on life, he's a good role model for the kids. They respect him," said Dennis Doyle, the center's director.

In 2006, Brown took transferable courses - with an eye on going to San Francisco State University - and ran successfully for City College student trustee. He later appeared in a TV commercial promoting City College and was keynote speaker at the college's 2007 graduation commencement.

As a champion for San Francisco's community college system and disadvantaged youth, he caught the attention of U.S. Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, whom he met at various events. They hit it off. This summer, he interned at Pelosi's San Francisco office, and traveled with her to Washington, D.C. He also traveled to Vietnam with City College's study abroad program.

"He can talk it up with the kids on the corner and two hours later he can be in a meeting with Nancy Pelosi. He's a true people person," Domiguez said.

Brown was accepted to San Francisco State, but his mentors at City College urged him to aim higher. Brown said they told him he was "Berkeley material."

"Derick has an ability to relate to many different types of people in a charismatic yet authentic and caring manner," said Don Griffin, City College's vice chancellor emeritus of academic affairs and a mentor to Brown. "Having studied at Cal myself, I knew it was the ideal university to nurture Derick's natural talents and inspire him further."

So he applied to UC Berkeley, and, to his utter amazement, got in.

Brown said he hopes to go to law school after getting his undergraduate degree at UC Berkeley. He's considering political science as a major.

"I'm using everything I learned out there on the streets, and in the gangs. I'm twisting that and putting it into education," said Brown.

And that success is what he wants for the kids he still mentors at the Juvenile Justice Center and the Boys & Girls Clubs, the ones who - through his example - know there's more to life than drugs, gangs and survival, and that it's theirs for the asking if they're prepared to do the work.

"They just need someone who can provide that example for them, and that's me," he said. "Education is the key."