Physicist Sumner Davis has died at 84

| 23 January 2009

BERKELEY — University of California, Berkeley, physicist Sumner P. Davis, a beloved teacher who devoted his life to the precise measurement of light emitted by molecules found in the sun and distant stars, died Dec. 31, 2008, at a care facility in El Cerrito, Calif., after a brief illness. He was 84.

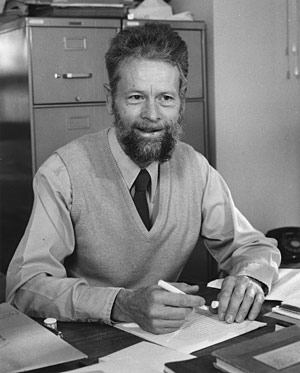

Sumner P. Davis in 1985. (LBNL photo)

Sumner P. Davis in 1985. (LBNL photo)Davis supervised 36 Ph.D. students during his career, all of whom became his lifelong friends, according to former student Joseph Reader, now director of the Atomic Spectroscopy Data Center at the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Gaithersburg, Md.

"Sumner was a favorite of the students and a very good teacher," said Reader, who was a student of Davis's in the 1960s. "He always had an extremely positive attitude, he was a can-do person."

Reader recalled Sumner's reaction when told that a vacuum pump that Reader had built exploded in the laboratory: "Well, now, we have to ask ourselves, 'What can we learn from this explosion?'"

"Sumner was a wonderful and devoted teacher and rescued many students from falling through the cracks of the department. He is greatly missed," said one of Davis's former undergraduate students, Bartley L. Cardon, now with the Lincoln Laboratory's Air and Missile Defense Technology Division at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Davis was very proud of the Distinguished Teaching Award he received from UC Berkeley in 1980, according to his wife, Robin Free. After his retirement in 1993, Davis returned to campus for another 10 years to direct the upper division physics teaching laboratory, Physics 111. He made his mark by narrating videos explaining to new students how to conduct the various experiments in the laboratory. These videos are still in use today.

The respect he showed students was reflected in his dealings with the occasional eccentric who called, wrote or visited the physics department to discuss some speculative new theory. Departmental staff would send such visitors to Davis, Free said. "He gave them his respect and time to listen to their wild ideas," she said, and even struck up a long-time friendship with one of them. "He got a kick out of it."

Davis was born March 18, 1924, in Burbank, Calif., and enrolled for one semester at UCLA before being inducted into the Army Air Corps during World War II. He trained to be a meteorologist at Pomona College, then switched to electronics and radio, eventually attending Yale and Harvard universities before graduating from MIT's famed Radar School. By then, however, the war had ended, and he left the Army to finish his A.B. in physics at UCLA in 1947.

While on the East Coast, Davis took flying lessons and remained an avid glider pilot around the West into his 80s. He and his glider were pictured in National Geographic magazine after he achieved an altitude record of 10,000-plus feet over Arizona. As recently as 2000, Davis served as president of the Pacific Soaring Council Inc., an organization devoted to furthering the education and development of soaring pilots.

After obtaining a master's degree from the University of Illinois in 1948, Davis entered graduate school at UC Berkeley, from which he obtained a Ph.D. in 1952 for work with molecular spectroscopist Francis Jenkins using measurements of atomic spectra to determine the nuclear spins of selenium isotopes.

He served as an instructor at MIT between 1952 and 1955, when he joined the research staff. In 1959, Jenkins invited Davis back to UC Berkeley to teach spectroscopy, and Davis joined the physics faculty in 1960. He was promoted to full professor in 1967.

Davis returned to UC Berkeley with a highly prized gift - a diffraction grating presented to him by MIT mentor George Harrison, the premier artisan of finely-ruled gratings that produce the best spectra anywhere. Davis used the grating for years as part of an echelle spectrometer to measure atomic spectra, although he also built a Fabry-Pérot interferometer to capture atomic spectra on film.

For much of his career, he studied the spectra of two-atom (diatomic) molecules of interest in astrophysics, working initially with UC Berkeley astronomer John G. Phillips. Among the molecules he discovered or cataloged in the laboratory, in stars or in the sun were C2, FeH, CS, SH and SiC2. He authored a book, "Diffraction Grating Spectrographs," in 1970, as well as books on CN and C2 spectra.

After Davis moved into Fourier transform spectroscopy in 1976, he frequently traveled to the National Solar Observatory at Kitt Peak, near Tucson, Ariz., to collect laboratory data using the observatory's spectrometer, then returned to UC Berkeley to analyze his measurements. He coauthored a book, "Fourier Transform Spectrometry" (2001) with Mark C. Abrams and the late James Brault.

Upon his second and final retirement from teaching in 2004, Davis moved from his home in El Cerrito to Tucson to be closer to the spectrometer. Two years later he moved back to California, settling in Carlsbad before returning to El Cerrito last year.

He was a fellow of the American Physical Society and the Optical Society of America, and a member of the American Astronomical Society and the American Association of Physics Teachers. Upon his retirement, he received the Berkeley Citation. He was a NATO Senior Fellow in Science in 1967 and twice was a visiting astronomer at the National Solar Observatory on Kitt Peak.

In addition to his love of gliding, he was an enthusiastic amateur oboist, according to his wife, and for several decades hosted weekly chamber music groups in his home where colleagues and students played together. He loved to build things, including a harpsichord, despite the fact that he couldn't play it.

"He was like a 10-year-old boy," Free said. "Every morning he would wake up and think, "What adventures am I going to have today?'"

Davis is survived by his wife, Robin Free, of El Cerrito, Calif., and a niece, Christine King, of Morgan Hill, Calif. His first wife, Grace, whom he married in 1947, died in an automobile accident in 1989.

In lieu of flowers, Free requests that donations be made to the Physics 111 Laboratory Improvement Fund, c/o Maria Hjelm, development officer, Department of Physics, 366 LeConte Hall, Berkeley, CA 94720-7300.