PUEBLA, MEXICO The divide between Mexican farmers and international policymakers was evident as soon as participants from the public attempted to pass security for the meeting of the North American Free Trade Agreement's (NAFTA's) Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC).

After I stepped through the metal detectors and stopped to pick up my backpack, I watched as a young, female member of the farming community attempted to do the same. She strode confidently through the metal detector, but the security team stopped her and confiscated her simple plastic bag filled with corn and tortillas - nothing threatening like guns or knives. The guards told her that such products were not allowed in the conference room. Another witness to the scene rolled her eyes in disgust, looked to the guards and, with an undeniable edge in her voice, declared, "It's not like it's genetically modified corn or something terrible like that!"

The stoic response from the faceless security guard? "All they told us was no corn."

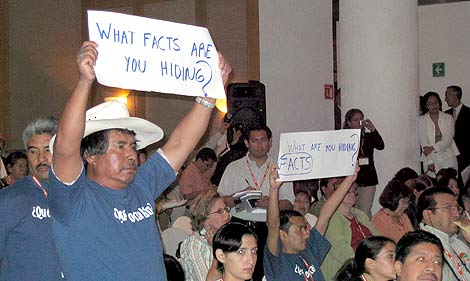

Members of the public wearing green shirts with "What are you hiding?" in Spanish infiltrated the meeting. |

Some apparently managed to smuggle the contraband in. Later, after the meeting had started, indigenous farmers wearing brightly colored shirts demanding "No más maíz trangenico!" ("No more transgenic corn!)" and "Qué ocultan? ("What are you hiding?") mobilized out of their seats. In a flurry of motion that generated undeniable energy in the meeting hall, they integrated themselves throughout the large audience and surrounded the CEC high council members seated at the front of the room.

Handing out the fresh tortillas for which their social movement has become famous, they chanted "Maíz, maíz!" and held up signs of protest. They were waiting for the CEC high council (made up of the environmental ministers of the three NAFTA nations) to respond to their public demands that the genetic material of their ancient strands of corn be protected. The demand has become more urgent as NAFTA's provisions increase the spread of genetically modified corn, which is cross-pollinating and contaminating indigenous corn.

In all the confusion, the Mexican Environmental minister accepted the tortillas, later declaring, "Somos maíz! ("We are corn!"). The U.S. representative from the Environmental Protection Agency, however, refused the tortillas, and in his response to public comments that had largely focused on the transgenic corn controversy, failed to acknowledge the issue at all. He showed blatant disregard for an issue that goes directly to the heart of social, economic and environmental changes undeniably linked to free trade.

This interaction between the people of Mexico and the high council provides a crucial lens for understanding how the CEC functions and why it is important as an international governing body. If nothing else, the CEC serves as a sounding board, offering frustrated citizens a place to voice their opinions on how free trade is changing their ways of life. From what I observed, however, the CEC is not necessarily a forum where public opinion actually matters - despite the CEC's original mandate to directly integrate public opinion into the policy-making process. Over the course of the meetings, it became clear how much the divide between the public and the policy process has widened.

Usually, the public appeals to the CEC central advisory committee (see About the Project), which is responsible for conveying the environmental concerns of the public to the high council of environmental ministers. There are precious few opportunities for the public to appeal directly to the ministers. On the contrary, at this meeting where both the ministers and the public were present, extensive security maintained a political and social hierarchy throughout the gathering, lending a special urgency to the few moments the public had to interact with the delegation. Finally, after their limited interaction with the public, the environmental ministers as well as the advisory committee must persuade the trade ministers of the three nations (a group never present at CEC meetings), to amend NAFTA to protect the environment from trade.

It's distressingly easy to see how 'public interest' gets lost on its way up the chain of command.

I was frustrated and saddened by the proceedings of the 11th annual CEC meeting for a number of complicated reasons. The first has to do with the notion of the "public." While the CEC has been deemed one of the most transparent international bodies around, one that does all that it can to invite the public to participate in its meetings, few "regular people" have the resources or even the knowledge of what the CEC is to generate an adequate and representative participant body. Thus, the scope of participation is immediately limited, and only a few select voices are heard. Second, although the CEC's advisory committee should act as the bridge between policy makers and the public, they are not only ill equipped to do so, but they also seem largely disinterested in fostering a true debate and discussion with the people who were present.

Even if the advisory committee had been more interested in working to incorporate public interests, they lack the power to initiate change or move proposals that would change the provisions of NAFTA. This translates into:

(1) A public with the desire and commitment to appeal to those in power, but that nevertheless lacks the resources, know-how and political connections to do so effectively

(2) A disinterested advisory committee that, with limited time to appreciate and adequately represent public desires on environmental and trade issues, still must write reports and make recommendations that supposedly reflect the public interest

(3) A high council of environmental ministers paying lip service to the plight of the public by listening to 20 minutes of public appeal, but ultimately serving no masters other than those above them, namely, the trade ministers of each of the three nations.

(4) The above result in a theoretically positive Commission for Environmental Cooperation that in practice is irrelevant.

These challenges are certainly not new for organizations that seek to build bridges across national borders and to incorporate the public in the process. Still, if the CEC is to move from a principled but toothless organization to one that truly shapes NAFTA's evolution, the hurdles are great. At present, it is clear that the CEC was not developed to have any meaningful or lasting powerful input in governing the environmental conditions affected by trade.

- Elizabeth