"Damn! Sex selection? Give me more Indian girls any day!"

It was impossible to keep my composure at several key moments during this focus group, but this comment in particular sent everyone in the room into convulsions of laughter. As part of my research, I was conducting a focus group with six South Asian American college students. The students came from three different institutions in the Bay Area, and all were born and raised in the Bay Area, although their families came from several different parts of India: Gujarat, Punjab, Tamil Nadu, Bengal, and Kerala. There were four men and two women in this particular focus group, and their insights and experiences of the way that gender structured their lives were particularly insightful. This was the third such focus group that I had conducted; this particular conversation was the most engaging of all three, mainly because the participants were very vocal about the issue of sex selection and underlying issues such as son preference and the status of South Asian women. The interview was only designed to last for one hour, but three hours into the conversation, the students were still lively and energetic in the questions they posed to each other and the humor they sometimes used in responding to the tougher questions. Although it took about 30 minutes for them to warm up to each other and to the process, once certain topics of discussion emerged, they piped up immediately, stumbling over their words and using hand gestures excitedly to emphasize their points.

"The thing is…you have to remember that our parents came from places where this was all accepted. It's kind of hard to criticize them, don't you think? When this was what they saw growing up?" This particular student was definitely the most vocal about sympathizing with the immigrant generation and understanding the circumstances, social and otherwise, that influenced their attitudes, perceptions, and practices. "Yeah, but some things are just f***ed up," responded a female student. "I have a cousin that got all this crap for having a girl, and I don't think there's any reason to justify that, you know? Like, am I any lesser than you just because you're a guy and I'm a girl? No. Then why does some relative think he or she has the right to make my mom feel lesser than your mom?"

Another student responded to the first point, saying, "But do you really think this stuff is accepted where our parents come from? I don't know…I feel like Kerala is all about equality. At least that's what I've read and that's what my parents tell me. So I don't know. Maybe it's not even something done so much in India."

A male student responded to her by saying, "I agree. It's weird to be having this conversation because I have literally never heard of this kind of son preference stuff. In my family, I think we were all treated pretty equally. My sisters couldn't do certain things, but I couldn't do those same things. Like dating and stuff. It wasn't allowed, so we all just snuck out and had each other's backs about when we did that kind of stuff. So it wasn't like I could have girlfriends and go out and party and do whatever I wanted, and my sisters couldn't. Or that I was the only one who was expected to go to college and my sisters were supposed to stay home. I think that Indian parents are more protective of their girls, but I think all parents are."

At this point, one girl turned to me and said, "I've definitely seen this in my family. I know of uncles who kept having kids till they had a boy. I don't think it's a regional thing, either, because we are also South Indian but not from Kerala. Do you think it has something to do with how parents are afraid to raise girls in the West? Do you think that that might be a reason why they don't want to have girls?" As much as I wanted to respond with my own observations, I threw the question open to the group instead.

There was a short silence, and then one of the boys spoke up. "I can see how that could be true. I think there's a lot more at stake when an Indian girl does something that her parents think is somehow…out of bounds or transgressive. …I mean, if a girl is caught doing something like having a boyfriend, I think people judge the family more than they would if a boy had a girlfriend. So in that way, I think, yeah, it must be different having a girl than a boy. But is that reason enough to actually go and have a doctor help you have a boy?" This comment set off a whole discussion about the inequity inherent in the different standards by which the equal actions of Indian girls and boys are judged by the family and community. Interestingly, all of the men in this group (and in the two others) acknowledged how unfair those double standards are, but they were unsure about the link between such double standards and medically assisted sex selection processes.

"It seems kind of extreme to go to all that trouble to have a boy or girl. How many people actually do this stuff?" one student asked. (The group really tended to ask me many questions, even calling me "Professor" at one point — which caused me to crack up laughing and tell them that I am only a few years older than they are, so the terms "Professor" and certainly "Auntie" should not be used with me!)

The description of such services as "extreme" was one of the main commonalities between the different focus groups. Additionally, focus group members expressed confusion about why this practice in particular survived South Asian immigrants' physical and cultural relocation to the West. "It's not something I can envision my family doing," one male student said. "I think issues like class and education are probably a part of these decisions, but even then…my uncles both work in factories, and I see how much they love my cousins. All my cousins are girls and I don't think anyone ever was upset about that."

|

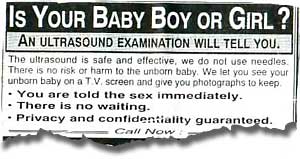

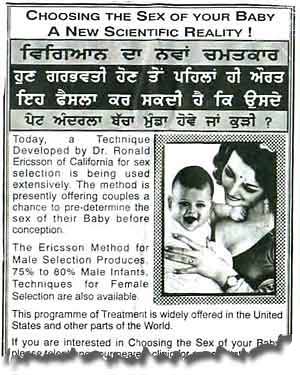

The tendency of students to examine their own families in the context of questions I posed was understandable, and it was actually remarkable to witness, across focus groups, the students' questioning of the ways in which class status, education, length of stay in the Bay Area, and family dynamics all might influence a couple's decision to sex select. There were no students who jumped to irrational conclusions of blame; all of them engaged with the possible reasons why a couple or family might make this decision. As a whole, with a few exceptions, each student exhibited concern over this trend in part because they had never before heard of this technology being used, and in part because of the advertisements appearing in South Asian publications. When I showed the advertisements to the students, I was very careful to excise any information revealing the identity of the physicians or clinical practices offering the advertised services.

|

At right is an example of one such ad from a South Asian newspaper. A portion of it is written in Gurmukhi, the script in which the Punjabi language is written. The students reacted to several aspects of this advertisement in particular. Many students were not familiar with the Gurmukhi script and could not recognize it; they could, however, recognize that the ad sought to market services to South Asians on the basis of the picture, in which a South Asian-looking woman (complete with a bindi) held a baby. They also pointed out that the ad made reference to success rates for conceiving a male child, but not a female child. When they learned that the script was Gurmukhi, they immediately had questions about whether the ad appeared in other South Asian languages and, if not, why not. I replied that I had not come across ads in other South Asian languages, although I had come across English-language ads in which providers of these services noted that they spoke South Asian languages including Hindi, Urdu, Gujarati, Punjabi, Marathi, and Tamil. The groups tended to ask me for more information about how people in the community felt about these ads and services being offered. I tried to steer clear of answering questions, partly because those are questions requiring far more research to answer, and partly because I felt the very fact that they were asking these questions was noteworthy and indicative of their own feelings towards the advertisements. Although there were many moments that I wanted to provide my own thoughts in answer to their questions, my opinions had to take a back seat to my role as facilitator.

Once I begin focus groups, rather than individual interviews, with women and families in the community, it will be interesting to note the differences in group dynamics and topics for discussion. The questions that I pose in groups are so linked to other cultural, social, and economic issues that group discussions become both fascinating and frustrating: the latter because it is difficult as the moderator to direct participants back to the central questions when all of the questions and underlying topics are of such interest! It is also extremely difficult to remain neutral and to make all participants feel comfortable expressing their divergent viewpoints; in my three experiences thus far moderating focus groups, I realize how many more skills I must acquire before I turn to moderating focus groups composed of South Asian immigrants, who will likely be far more concerned about issues of confidentiality and who will be less likely to speak candidly of their own families and individual experiences.

I felt it extremely important to include the voices of South Asian American youth in my research not only because of their important place in the community, but also because their experiences and suggestions are valuable for the directions in which I take my research and the way in which I refine my work to include new questions and audiences. It was an absolute privilege to be able to pose questions to these groups of students and to observe the ways in which they created a rapport with each other, debated each other respectfully, and tried to put themselves in the place of couples seeking out these technologies. Although this sample of respondents is certainly biased in that it was a largely self-selected group intrigued by the topic of my work, it was interesting to note that there were actually more men than women in the three groups of respondents and that they were equally eager to explore the ways in which male violence against women and male subjugation of South Asian women were important factors to consider when discussing gender selection. These moments were among the most heartening during my interviews, for they revealed to me that at least some South Asian men were starting to be more vocal about issues that affect their sisters, mothers, and friends.

I hope that I can continue to engage my generation in important efforts of community building, understanding the struggles of first-generation immigrants, and responding to those struggles with sensitivity and understanding. Since I hope that this research will be used in part for the purposes of community building and dialogue within the community, it is my hope that I left the focus group participants with a series of questions to ponder, answers to search for, and dialogue to begin.

—Sunita

Sunita Puri is a 2005 Summer Fellow of UC Berkeley's Human Rights Center.