BETHLEHEM – I head over to the D'heisheh Refugee Camp late in the evening to meet with some doctors and nurses in the Ib'da Cultural Center to discuss the project. As I come near the entrance, we pass some dumpsters with U.N. markings that are absolutely the worst things I've ever smelled in my life. Some stray cats are scrounging around in them for food. To make matters worse, I have my window open in the car, and there is sewage water on the street. As we're driving, some of the water splashes through the window and hits my face. As soon as we arrive at the center, I hurry to the bathroom and wash my face with soap and water, thinking about the poor people who actually have to live in such conditions.

The center is a four-story, recently constructed building with dormitories, meeting rooms, an auditorium and a restaurant on the fourth floor. After entering, you are immediately in the stairwell, which is completely painted with murals all the way up to the fourth floor. The murals depict images of a young Palestinian fighter slinging a Molotov cocktail, a group of tents with important dates on them to symbolize the creation of the Palestinian refugees, and Palestinians engaged in traditional dances.

When I enter the restaurant, I am greeted by some of the nurses and doctors that will be helping tomorrow. We talk about the project and make some last-minute adjustments to the program, and then socialize for about half an hour. One of things we discuss is whether or not to change the program from the earlier Bethelehem project session, and ask people to come fasting, not having eaten breakfast. We ultimately decide to invite the people fasting, but we move the start time of the project to 8 a.m., so that they can go home and eat after the program.

As I am getting ready to leave, a college-aged boy named Abdullah starts to talk with me. Apparently, he has taken a liking to me, as every time I see him, he always comes and greets me. He is about 5'10," with a dark complexion, wearing his long black hair in a barrette and bearing a real similarity to the picture of Marxist Revolutionary Che Guevara that he wears around his neck. I get asked the question about which is better – America or Palestine – maybe for the fiftieth time. Again, I try to answer diplomatically by saying that both are nice places in different ways. I explain that in Palestine, there may not be the most modern buildings and large attractions that the mega-cities of the U.S. have to offer, and that living under occupation is certainly not the most favorable of circumstances. However, I point out that the most attractive aspect about living in Palestine is the warm hospitality of Palestinians towards each other and strangers, and the close family structure, which is an integral part of Palestinian society. I explain that in the United States, it is very common for both parents to work full-time, and for relatives to live clear across the country and not see each other for years on end. In contrast, the Palestinian family lives in the same town, sometimes even in the same building, and a close family structure is valued not only for support in raising children, but also for creating a strong family presence in the community.

After chatting for a few minutes more, I leave the center in the dark. My driver and I take a ride through the camp at night, coincidentally behind one of the new Palestinian police cars. They are brand new Volkswagen Jettas, painted baby blue with flashing blue lights on top. They always drive around with their lights on, whether there is an emergency or not, to establish their presence (I think). Most Palestinians do not pay much attention to the police because they have been living without a strong police force and government presence for many years, some Palestinians see them as untrained and unskilled, and still others see them as corrupt.

The houses in the D'heisheh Refugee Camp are made from hurriedly-constructed concrete and stone walls and are far enough from each other to allow only space for one car to pass. The streets are dirty from cars and discarded food from street vendors' carts. People are still meandering along the streets and make way for us as we drive. It's really like a maze. We have to ask a few people how to get out of the camp, and they tell us to keep going straight until we finally exit.

THE NEXT MORNING:

I wake up at 7 a.m., get dressed, put the supplies in the car and head back over to D'heisheh. We had arranged for the health committee members at the cultural center to use their list of already diagnosed diabetics or at-risk patients in inviting people to attend. I thought it would be interesting to compare the Bethlehem project, where we announced that both diabetics and non-diabetics could attend, and this project, which targets at-risk and previously diagnosed diabetics.

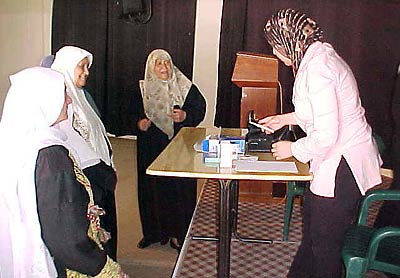

Unlike the Bethlehem participants, most people arrive on time and sit in the waiting area. We call them into rooms where we have our testing stations, and they are each tested by the volunteer nurses. Although I have done a few demonstrations of the machines the day before, some of the volunteers still have some trouble, but are quickly helped by their colleagues. Using the monitors, the nurses show each participant how to use them and take everyone's blood sugar levels. After each person's reading is recorded, they are asked to go upstairs and wait in the auditorium. Having scanned the list of names, it is very clear that these diabetics, like many others I've encountered, are not managing their diabetes properly. They have very high readings.

The nurses, knowing each patient's type of diabetes and conditions, give them some insulin obtained from UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees). The nurses then serve the participants some wheat bread and tea with no sugar. Most of the participants are women in traditional Palestinian embroidered dress, wearing white headscarves or hijabs. There are a few men and three children.

After the food break, I again speak to the audience, telling them about my motivation for starting the Micro-Clinic Project and its main purpose. I then yield the floor to the five speakers; they cover diabetes-related topics, like causes and effects, management and treatment, care and complications, and diet and exercise. Again, as in the Bethlehem project, people are not satisfied to listen; they have many questions and enjoy interacting with the speakers.

During the lectures, some of the men in the audience start smoking – a habit which is not good for anyone, especially diabetics. Despite my mentioning the problem to some of the volunteers, it is impossible for us to do anything about it. When I visit people's homes, I feel asphyxiated from the constant smoking of the men; sadly, many are holding their babies as well. But everyone here sees it as absolutely normal, and they think I'm crazy when I tell them that, in California, we cannot even smoke within 15 feet of some buildings. Perhaps the next Micro-Clinic Project will be about smoking!

After the lectures finish, we thank the participants for coming and tell them that we will be in contact with some of them later in the week. We do not promise machines, because the center will become swamped with requests. The nurses and I meet upstairs in the restaurant to look at the results from the testing. From this data, we will make our decisions about how to form the groups and distribute the machines in the micro-clinics later in the week. We decide that Type 1 diabetics and children will have priority. We have also obtained some information as to who already has access to machines.

I then take a walking tour of the camp with the doctor and nurses and visit some of the center's facilities, including an unfinished building that will house a new health care center. According to the volunteers, this facility is critical to the well-being of the community. It will provide preventative measures, as opposed to the medicine distribution practice of the UNRWA. Furthermore, one doctor explained that an average doctor in the UNRWA sees about 170 patients a day, and therefore cannot do much other than hand out medicine.

As we end the tour, the volunteers thank me for the project, and I thank them for all of their hard work and effort which made the day a huge success. They tell me this was the first time they had ever done an educational outreach program for a large group of people. I anticipate that in the coming days we will be able to start distributing the machines and establish many new micro-clinics in the camp.

—Daniel