A new memoir by Paula Fass, the Margaret Byrne Professor of History at Berkeley, traces her past as the daughter of Holocaust survivors as a way of understanding their history and passing it on to future generations.

A new memoir by Paula Fass, the Margaret Byrne Professor of History at Berkeley, traces her past as the daughter of Holocaust survivors as a way of understanding their history and passing it on to future generations. A painful journey through the past

Tracing her family's Holocaust story, a historian learns that facts can count for as much as the big picture

| 26 February 2009

BERKELEY —Paula Fass always knew that she existed only because her parents, Polish Jews, survived the Holocaust.

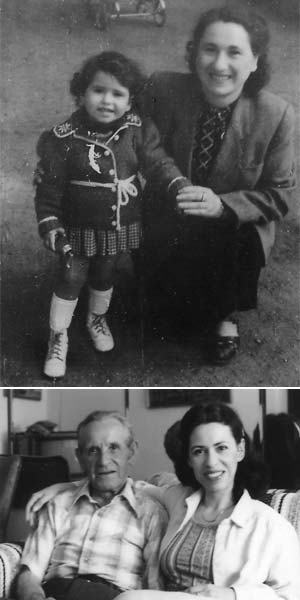

The memories of Professor Fass' mother, Bluma Sieradzki Fass (seen here with 2-year-old Paula in Germany in 1949) are the source of much of the personal history laid out in the historian's new book. Her father, Chaim Harry Fass (seen here with Paula in a 1983 photo), was less willing to bring up old memories.

The memories of Professor Fass' mother, Bluma Sieradzki Fass (seen here with 2-year-old Paula in Germany in 1949) are the source of much of the personal history laid out in the historian's new book. Her father, Chaim Harry Fass (seen here with Paula in a 1983 photo), was less willing to bring up old memories.Before she turned three, she had heard her mother's story of losing her son to the Nazi exterminators.

She was just seven, or so, when she discovered that her father had had an entire first family — a wife, two daughters, and two sons, all starved and weakened in the Lodz ghetto, then gassed at Auschwitz. He never spoke to her of them.

Fass, a Berkeley history professor for more than 30 years, now realizes that it's no coincidence that she went on to become a top scholar in the study of children — but always other children, never the ones that haunted her family. Not until her own children, Bibi and Charlie, were well into their teens did she turn her historian's eye to these ghosts.

The result was a deeply personal and often painful nine-year journey that started in Poland and is recounted in Fass's new book, Inheriting the Holocaust: A Second-Generation Memoir, just out from Rutgers University Press.

"I was very reluctant to do it for a long time. I felt like a poacher. These were not my experiences," Fass says. "Then I realized that it was my story, and that I had an obligation and a responsibility to tell it."

While she hadn't lived her parents' lives, she had been shaped by their memories and their pain — and she wanted to know their lived experience, and understand it better, so that she could pass the connection along to the next generation.

"It needed to be real for my children, so they had a past," Fass says. "And I needed it to be real for other people, as well."

The enormity of the Holocaust is so immense that it's hard for the mind to grasp, she says, unless you shatter it, like a huge piece of glass, and tell it through the pieces, the individual lives.

She builds her story through the everyday details she gleaned from the memories her mother, a gifted storyteller, shared with her and from the fragmentary and sometimes contradictory records she tracked down on an emotional journey to Poland nine years ago.

Fass was able to piece together the lives of several generations of her family — what they wore and ate, their jobs and friends, how they lived, first as thriving members of society in pre-war Lodz, then through the Holocaust's devastation, and then, for the few survivors, in their new lives. (A family tree in the book shows 20 family members lost — with the fate of others still unknown.) Her parents immigrated to New York, where Fass grew up.

Fass herself is a main character: The book is framed by her dual existence as the devoted daughter of survivors and a young American teen-ager building her own identity as a scholar while grappling with questions about the role memories play in constructing history.

Neither of her parents ever went back to Poland before they died. They didn't want to. But Fass realized that if she were going to write her memoir, she needed to start there. She was born in Germany, where her parents were liberated, in 1947, landed in New York in 1951, and went to Poland for the first time in 2000, accompanied by her daughter, Bibi.

Her profession gave her the tools she needed to find the facts amid what remains some six decades after the Nazi atrocities were ended: birth certificates and graves, so many unmarked; the register from the Jewish ghetto in Lodz, where her parents lived through much of World War II; notebooks of people from the time. Fass, with Bibi, walked miles in the Lodz cemetery looking fruitlessly for her two grandfathers, who had died of starvation in the ghetto.

At Chelmno, several hours from Lodz, she found a piece of history never mentioned by her parents, an early killing ground where many from Lodz — including, probably, Fass's mother's young son — perished. As Fass describes it, thousands "were gassed in large vans … and then dumped into the ground where we now stood. As the earth swelled with the rank putrefaction of so many bodies buried at once, the Germans sought more efficient and hygienic means of disposal."

Professor Fass' father, Harry (second from right in this photo), lost his first wife (far left) and their four children to the Nazis at Auschwitz. He rarely spoke of them again; Fass herself sobbed while writing the 'tormented' chapter in her book that tells their story.

Professor Fass' father, Harry (second from right in this photo), lost his first wife (far left) and their four children to the Nazis at Auschwitz. He rarely spoke of them again; Fass herself sobbed while writing the 'tormented' chapter in her book that tells their story. It was in Poland, after her parents' deaths, that Fass finally learned the names of many of the people whose stories she'd long heard — including all of the names of her father's four children and wife, and of her mother's first husband, who died in the Lodz ghetto.

As painful as her family's history was to recollect, Fass sobbed only as she wrote her chapter on her parents' first families. "It's a tormented chapter … the others are painful but not tormented," she says.

Mysteries remain, including how her parents survived what so many others didn't, and how they met. They didn't speak of it.

Writing the book was not, as some have suggested, cathartic for Fass. "In some ways it's the opposite," she relates. "I wake up in the night and passages of the book come into my mind, as if they're something I need to work through. It's almost as though I've finally allowed it to enter into my consciousness and my life. It's not separate now."

Writing the book also transformed her definition of the historian's proper role. Until she took on her family's history, she believed that a historian's primary responsibility was to interpret events, not simply to uncover what happened.

"Facts were only facts, but as historians we emphasize context and perspective," she writes. "Now I know that in trying to reconnect to this most essential history, the facts count the most."

Fass will read from Inheriting the Holocaust on Monday, March 2, at 7 p.m. at Black Oak Books in Berkeley.