Insect in hemlock forests causes loss of canopy, gain of invasive plants

| 26 May 2009

BERKELEY — Deep in the hemlock forests of the Eastern United States, a tiny, aphid-like insect may be playing a giant role in transforming an ecosystem, according to new research by ecologists at the University of California, Berkeley.

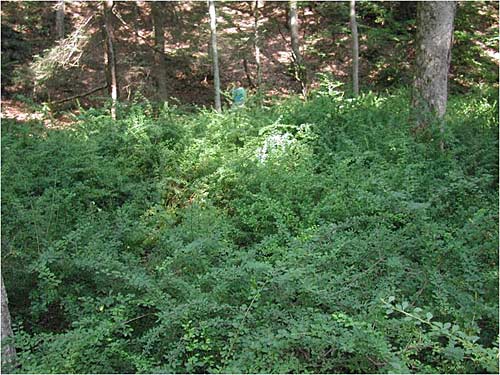

The understory environment of hemlock forests, characterized by uniformly low light levels and little plant cover, has been significantly altered by the decline of the hemlock canopy caused by an exotic pest, the hemlock woolly adelgid. (Anne Eschtruth photo)

The understory environment of hemlock forests, characterized by uniformly low light levels and little plant cover, has been significantly altered by the decline of the hemlock canopy caused by an exotic pest, the hemlock woolly adelgid. (Anne Eschtruth photo)The new study has found that this loss of canopy is also setting the stage for the successful invasion of non-native plants. The canopy decline leads to even greater invasion of non-native plants when combined with a high concentration of the plants' seeds and white-tailed deer in the affected area.

"This study provides important information for the management of natural resources," said study co-author John Battles, UC Berkeley associate professor of ecosystem sciences. "Knowing which factors to target in reducing the populations of invasive plants helps ensure that limited resources are being used effectively and efficiently."

Changing the amount of light filtering through the forest canopy has a particularly large impact on the unusually dark ecosystems of eastern hemlock forests, the researchers said.

The invasion of Japanese barberry seen in this photo has been accelerated by the decline of the hemlock canopy and by high densities of white-tailed deer. (Natalie Solomonoff photo)

The invasion of Japanese barberry seen in this photo has been accelerated by the decline of the hemlock canopy and by high densities of white-tailed deer. (Natalie Solomonoff photo)The study, published in the May/June issue of the journal Ecological Monographs, assessed the relative importance of canopy loss along with the consumption of plants by white-tailed deer, the diversity of native plant species and the concentration of seeds from exotic plants.

Determining which factors were most important in predicting the success of exotic plant invasion involved the use of data-intensive statistical models that examined results from 400 plots in 10 hemlock forests that were collected from 2003 to 2006.

"Many studies have documented the importance of each of these factors separately, but no other study has examined these four factors simultaneously and ranked their relative importance, which is what we really want to know," said Eschtruth.

The researchers focused on three abundant and aggressive exotic plant species: Garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata), Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii) and Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum).

They found that for all three invasive plants to succeed, canopy disturbance and seed availability were the most important factors. Moreover, when those factors combine forces, they magnify each other's effects.

The study also found that the white-tailed deer's preferential dining on native plants gave a significant advantage to garlic mustard and Japanese barberry, which each thrived when its competition was eaten.

And contrary to the theory that diverse ecosystems are less susceptible to invasion, the study found that species richness was the least important predictor of invasion for all three exotic plants studied.

The implications of the hemlock woolly adelgid's impact on canopy disturbance go beyond the introduction of new plant species, the authors noted. Eschtruth pointed out that the loss of the hemlock canopy not only affects the native birds and plants in the hemlock forests, but also brook trout and other aquatic life that thrive in the cooler temperature of shaded streams.